” ‘I came because I wanted to be with you, Lara. I could go back tonight if I wanted to.’ In fact he wanted to share a taste of danger with her. To descend as far, to take as much of her as he could survive, and risk even more. ‘Are you mine in the ranks of death?’ she asked, laughing.”

This theme of vitalism is central to the novel Bay of Souls. It is a brilliant book, pleasurable to read as it imparts an important message. The story deals with the question of what it means to seek out a more intense form of existence. And the way Stone tells the story is appropriate for this theme. The book is brief. It hits hard. Stone selects precisely the right episodes that are necessary to move the book from the placid, domestic scene at the beginning to the desolation of its ending.

The protagonist is Michael Ahearn. His dilemmas are in a sense unique in that as a university professor he belongs to a privileged class and therefore is open to certain problems that wouldn’t occur to others with less leisure or less opportunity to the plagued by existential doubts and anxiety. But there are hints that Stone intends us to read Michael as an everyman. And that is to see the central character’s sickness unto death as a symptom fundamental to our social arrangement in late capitalism.

The problem is an old one. William James deals with it in his essay concerning the necessity of finding a moral equivalent to war. It seems that our species has a biological predisposition to find fulfillment in strife. In taking risks and facing conflict. This feature of our minds is understandable when we consider the dangers and contingencies that homo-sapiens faced throughout the millions of years of being at odds with the natural world. Now, however, the lust for danger is precisely what won’t help us survive but threaten us. The need to take risks and face intensity is exactly that which threatens civilization, which is the organized way we’ve found to confront nature as a whole. And so, our ancestors, comprehending the threat that the passions played, wrapped tight bounds of taboo around our passions. This is represented in the novel by Michael Ahearn’s wife Kirstin who had a strict Lutheran father. He commanded respect for his disciplined and unyielding character. Even in death he casts a deep shadow over Kirstin and her mother. Michael resents this.

Nietzsche remarks that the repression of the ancient Christians was a source of immense power. It allowed them to win Europe over to their ideology for thousands of years. The successful repression and sublimation of the instincts for passion and violence led to certainty, to decisiveness utterly alien to the characters of men and women in later modernity. And this uncertainly, this confusion about just where commitment should be placed, is exacerbated by the technological end for the need of even physical exertion, let alone risk-taking, in all but a small number of specialized occupations. Enter the structural surrogates for a heightened existence that are the props of Bay of Souls: recreational hunting, unblended whisky, cocaine, not to mention sexual encounters involving loaded firearms and choke-straps. But the novel interests us not for what is said, for its licentious or salacious elements, as much as for the way it is said.

Stone has put together another of his well-constructed novels. It follows Children of Light, Dog Soldiers, A Flag for Sunrise, Damascus Gate and others no less worthwhile. Stone’s artistic approach is to write a narrative that imitates reality. It is sometimes called “realism” – although this name can be misleading if in using it we forget that “realistic” literature is every bit as conventional as a sestina or a madrigal. What is true is that this mode of writing bears a resemblance to some of the categories our social arrangement obligates us to place on daily life. Otherwise, Derrida is correct in his criticism that “realism” shouldn’t be understood as a form of writing closer to real life itself than other literary genres. To think this way is to believe an illusion.

And the realist illusion, beginning as a response to modernism in the 19th century, is very much the tradition that Stone is writing in. Bay of Souls has its antecedents in Russian writes like Turgenev and Chekov, the later in Zola and Conrad, and as we move into the 20th century in Hemingway, Greene – with perhaps Stone’s most similar contemporary being Denis Johnson, whose work Tree of Smoke is exceedingly suitable to go alongside Bay of Souls and Damascus Gate.

Bay of Souls challenges the bias against realism which contends that it is a shallow form of literature. The claim is that in attempting to render life as it really is, by rooting the narrative in the unified structure of time, place and horizon of expectation, it doesn’t really get to the core of truth about life. And it is for this reason that realism as a form lends itself so well to entertainment consumer novels – Tom Clancy or V.C. Andrews, good reads that provide distraction and won’t worry their anxiety ridden audience with any disturbing demands on their intellect or moral sense. Obviously there is truth to this, but Bay of Souls and the other writers mentioned above, even Greene in novels like Brighton Rock or A Burnt-Out Case are subversive of this expectation of realistic literature. Bay of Souls is from the first few pages fortified with heavy themes. Stone doesn’t hesitate to openly meditate on religious questions. And whatever the suspicion about this might be, this isn’t speculation along the lines of Dan Brown. Stone’s purpose, a part from supplying that nebulous “aesthetic experience”, is to tell us that religion is still a very large question mark in our lives. That is while religion has been dealt with and no longer seems an issue for a larger part of society than ever before, in reality it is still a going concern.

In this novel of violence, of the fraying away of order in life and of irresponsible solutions to pressing imperatives, there are two major treatments of the theme of religion. The first relates to the way that life seems to have become strictly utilitarian. Something that might sloppily be called “the sacred” or more specifically a feeling for the intrinsic value of things has been lost to the characters of Bay of Souls. Marriages and friendships dissolve and reform based on the caprice or whim of the parties involved. One opening scene eerily depicts the carcasses of deer filing the neighborhood streets of the small town where Michael Ahearn teaches. Most poignant of all is the vision Michael has of a half-crazed man pushing an over-sized carcass along in an under-sized wheel barrow. This happens in the stillness of the forest and is a terrifying foreshadowing of the events to come in the novel. This is also true of the flashlight Michael drops into the river during that same hunting trip. They see the flashlight at the bottom of the river, “soldiering on” weirdly illuminating the depths.

It is down to the depths that Michael is going to have to go during the crisis of the novel. He dives down to retrieve some lost items from a plane wreck, submerged on a reef. This section is written in the typography of the classical “katabasis” or descent to the underworld that the hero undertakes in poetic works like the Odyssey, the Aeneid, the Pharsalia and, of course The Divine Comedy. But unlike the underworld episodes of those narratives, the dead don’t speak to Michael. He sees a corpse being slowly devoured by fish, yet this vision only reminds him how thin is the veneer over life’s terrifying potential. He risks being trapped in plane, which might easily go sliding off into the Puerto Rican trench. This trench represents the sum of all fear in the novel. The absence of anything that distantly drives the characters to seek out consolation is pleasure or rigid stricture.

The world of Bay of Souls resembles our world in that it seems entirely physical, material, the world as described in standard grade 12 physics, chemistry and biology books. The dilemma Bay of Souls presents is that this inert, material world presents a contradiction to the human spirit. To live a complete and fulfilling life, do we need to believe in something more than materialism. Should we not make room for the ecstatic, the fantastical, for the loss of self in Bacchanalian rites, of the kind the closing chapters of Bay of Souls?

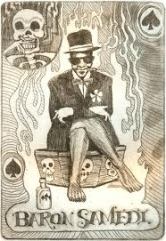

Stone seems to answer in the affirmative. He does so by further undermining the standards of realism by presenting possession as ontologically real in the novel. Baron Samedi or Gede seems to be real. Baron Samedi possess characters in the novel at will and alludes to events in Michael’s life. The novel thus becomes, at the end, a fantasy novel. Stone seems to be suggesting that there really is something out there, a spiritual reality beyond or usual comprehension. And it is in reaching this that Michael fails. He loses the spiritual potential for his life by trying to save his life at the end of the novel. A final vision of Lara, who had been a kind of slutty version of Beatrice throughout the novel, informs him that he failed because he wasn’t able to surrender himself completely to the mysteries she offered him initiation into.

Bibliophilia Obscura

Bibliophilia Obscura Goodreads

Goodreads The Modern Word

The Modern Word